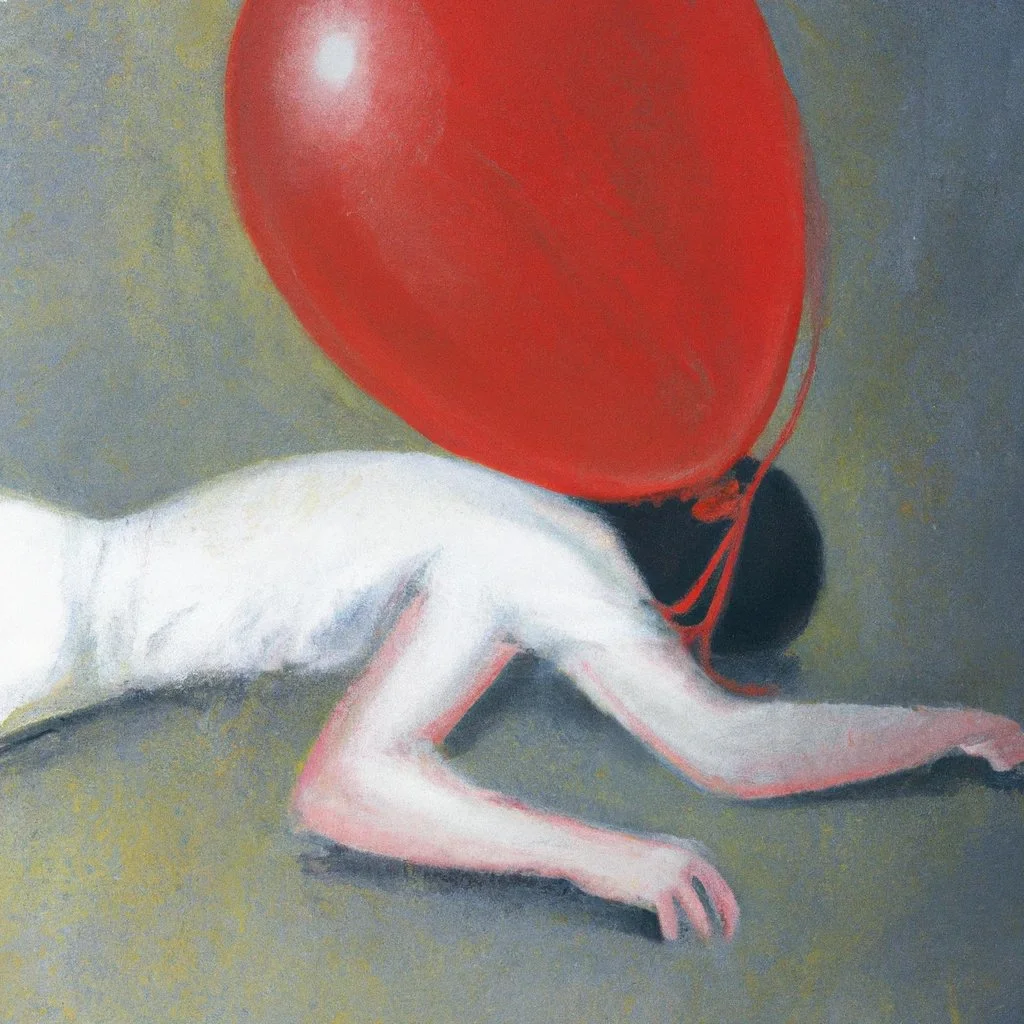

Image: Deflated

Julie Kirsch via DALLE-2

Many of us are full of uncertainty, if not doom and gloom, in response to developments in artificial intelligence. We fear that technology, like ChatGPT, will undermine higher education and eliminate jobs for journalists, grant writers, and computer programmers. Moreover, as this technology improves and expands, it could pose an even greater threat to our economy and way of life. Those working in the arts are not immune to these threats. We often think of the arts as involving all that is uniquely human—deep and complex emotions, creative or original compositions, and the expression of own inner experiences. But AI art generators like DALLE-2, have prompted many of us to wonder whether even this near sacred aspect of human life will be overtaken by AI. As captain of team doom and gloom myself, I do not take these fears to be groundless or exaggerated. In what follows, I will look at how the AI revolution may play out and adversely affect artists and other creative professionals in the near and distant future.

Let me begin by stating the obvious: what we are seeing is just the beginning of the AI revolution. We are currently interacting with an early version of the technology. We should expect that subsequent versions will be far superior to what we see now. In my last post, I commented upon the current limitations of the technology and the sometimes-cartoonish quality of the images that it produces. Future iterations of the technology will undoubtedly address these limitations, producing increasingly impressive and nuanced imagery.

As the technology improves, it will likely become increasingly popular with ordinary folk as well as those in the business sector. In some respects, this may appear to be a good thing – a boon for small business owners who might not have the funds to hire a graphic designer. But as businesses of various stripes view the use of the technology as another cost-cutting measure—a way to lower expenses and increase profits—jobs for graphic designers will disappear. And, for similar reasons, jobs for photographers, illustrators, etc., will also disappear. Why would a corporation hire a graphic designer when they can use an AI art generator for little to no cost? Why would a publishing company hire an illustrator when they can create their own illustrations by plugging text prompts into a free or inexpensive app?

To be sure, it is possible that those making business decisions of this sort will be motivated by the goodness of their hearts to do the right thing and support struggling artists, but this seems unlikely. That’s not how corporations operate. Heck, that’s not even how most ordinary people operate. We gleefully buy environmentally destructive clothing from underpaid, ill-treated workers because it’s less expensive than clothing made from organic cotton by appropriately paid workers who are treated with decency. And it’s common for the person on the street to purchase a mass-produced piece of artwork from TJ Maxx or Target because they do not want to dole out the cash for an original work of art by a living artist (even if they can afford to do so). Moreover, they buy the mass-produced wall decor knowing that a professional artist’s livelihood depends upon their ability to sell their work. There are, of course, countless exceptions, but we must not have unrealistic expectations of our fellow humans (and of ourselves).

All of this seems especially problematic when we consider that AI art generators are trained upon the original works of art that are fed to them by artists and creative professionals that are struggling to hang on. After the AI learns the style of a certain illustrator, it becomes possible for it to produce a new work in that style, thereby rendering the living, breathing artist otiose. This has prompted some creative professionals to ban together in opposition to this technology. Led by writer and illustrator, Molly Crabapple, a group of artists, writers, and cultural luminaries published an open letter, urging companies to boycott the use of AI-generated images (Lawson-Tancred). The letter describes AI art as vampirical, “feasting on past generations of artwork even as it sucks the lifeblood from living artists” (Center for Artistic Inquiry and Reporting). It argues that the use of AI-generated images will boost the profits of our wealthy corporate overlords while making it nearly impossible for professional human illustrators to survive. Unless we intervene, only a small group of elite artists will remain in business, selling their work “as a kind of luxury status symbol.”

Importantly, the letter asks us to consider what this will mean for our culture—for humanity—and not just for the professional creatives that eliminates. It warns that, unless we intervene, the technology will “impoverish our visual culture.” We, as consumers, “will be trained to accept this art-looking art, but the ingenuity, the personal vision, the individual sensibility, the humanity will be missing” (Center for Artistic Inquiry and Reporting).

I don’t take the letter to be alarmist, or the claims to be an exaggeration, especially since AI-generated illustrations are already in print. The only point about which I would quibble is the claim that AI-generated art would lack “wit.” Some AI art can indeed be quite “clever.” And as forms of artificial intelligence become increasingly sophisticated and humanlike, we may be more willing to use terms like “wit” to describe its inventions. But this raises philosophical questions that, while important, are beyond the scope of this post. (I will perhaps take them up another time.) The letter is right, of course, in claiming that imagery produced by an AI will lack a personal vision or individual sensibility. What many of us love and cherish in a work of art—an illustration, drawing, painting, or photograph—is just this. While an AI art generator may rapidly produce illustrations that resemble Crabapple’s, it may matter a great deal to me that I have the real thing—that Crabapple’s brain produced it.

Many of us value works of art, not just because of their surface value or qualities, but because of their connection to real, flesh and blood human beings. This may in part be because we love and cherish human beings themselves; we are concerned and fascinated by them. While we may be intrigued by paintings that resemble Van Gogh’s, or by paintings that he might have created, we care more about the paintings that he actually did create with his own body and mind—paintings connected to his own life story, heart, and hand. This also accounts for why some of us want, or would love, to own original paintings by artists whom we admire. While art buyers may in some cases want an artist’s original work for reasons of status, or because they admire the shear physicality of the piece (brushwork, texture, luminosity, etc.), in other cases they may want the original for reasons that are almost sentimental or romantic. We may value an original work of art because, like an ancient relic or a lover’s lock of hair, it is a precious part of a one-of-a-kind, statistically improbable, flesh and blood life.

Each time that we trade what is beautiful, meaningful, and hard for what is hollow, cheap, and expedient, the world becomes a little bit less good. When we send a convenient text message in place of a hand-written thank you letter, we deprive the world of something special—something of greater value. When corporations replace human illustrators with AIs, thereby rendering human illustrators extinct, they change the structure and substance of the world. They make it less good.

I am not suggesting here that human beings would cease to be creative if AIs replaced all creative professionals. Human beings would continue to be creative and imaginative. However, when creative and imaginative human beings cannot devote themselves to their craft or calling in the way that a professional can, their ability to produce works of high quality is impaired. When would-be illustrators work 50 hours per week to pay their bills, only finding time to create on Sundays between 2 and 4pm, their ability to produce works of quality is significantly diminished. There is no time left at the end of the week, or at the end of a life, to hone one’s skills, master a craft, or cultivate a creative vision.

Now, fears have long existed that machines will overtake human beings and leave us destitute and unemployed. The rejoinder has always been that as certain jobs are eliminated, others (often better and more fulfilling ones) are created. But it would, I think, be foolish to accept this as an a priori truth. In the past, this may have been true because jobs that required uniquely human talents and abilities always survived. But recent advances in AI suggest that jobs that require skills that many of us take to be quintessentially human, may be taken over by AIs. And after that happens, what is left?

In keeping with doom and gloom spirit of this post, I would like to end with one final existential fear. After AI art generators improve, and can do what we do with astonishing speed and skill, what will we make of ourselves and our own lives? When they can write poetry, paint portraits (with robotic arms, perhaps), and compose symphonies in a way that seems to dwarf our own accomplishments, will we come to see our lives as futile? Will we no longer bother to create and share our visions and longings with each other in the form of art? Will we be overcome by a sense of despair and meaninglessness? I suppose that there will be new drugs on the market to treat us for that.

I can say, though, that when I started to take piano lessons at the age of 45, it was not so that I could be the next Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart or Martha Argerich. Instead, I decided to take up the piano because I wanted to learn more about music, explore a new form of personal expression, and cultivate a different potential. Similarly, many people play chess knowing that there is a computer out there that can beat them – that they will never outsmart an AI. We don’t have to be the best at something to find it worth doing. And while we are here on Earth, we must do something. I nevertheless fear that, should AI surpass us in nearly every respect, many of us will find life to be futile and meaningless; we just won’t bother to do what AI can do better and faster. (To be sure, another possibility is that we ourselves will merge with AI in ways that Ray Kurzweil envisions, becoming cognitively enhanced superhumans.)

If AI surpasses us in art, music, and poetry, perhaps we will find comfort in our shared finitude and fragility. We will have compassion for each other, and want to connect with each other, not because we are all the best at what we do, but because we are given a hard lot, and each have a unique perspective on how we manage the ordeal.

Readers of this blog can expect my next post to be more optimistic than this one! I want to look at some of the ways that artists are embracing developments in AI and incorporating them into their art-making practice.

Works Cited:

“Restrict AI Illustration from Publishing: An Open Letter,” Center for Artistic Inquiry and Reporting, May 2, 2023. Accessed June 24, 2023.